Lessons Learned From Surviving A Flash Flood In The Grand Canyon

A similar article was published on the NRS Duct Tape Diaries blog (with extra photos!).

The below version is extended to share the play-by-play of the incident for those interested.

Everyone calls a river trip through the Grand Canyon “life-changing.”

It’s weeks of remote whitewater between towering sandstone walls, the ultimate blend of serenity and thrill. Wild desert forges bonds that flow beyond the steady stream of notification pings that have come to define every day “connection.” When I got the coveted chance to join a trip, I expected a personal transformation. I just didn’t know what it would entail.

View from the Nankoweap Granaries

Day 13 of 21 included a much-anticipated side hike. We pulled into Havasu Canyon, marveling at the creek’s pale aqua, an exciting contrast to the Colorado’s brown. Those of us hiking to Beaver Falls, 5.5 miles up the canyon, knew we’d have to hustle to make 3 hours round-trip.

It was a mild day. I swam through the mouth of the canyon to the trailhead in my sun hoodie, leggings, and sandals, figuring I’d dry soon. My partner B and I hiked quickly, the trailside water gradually turning less blue, then brown. We shrugged, hoping the waterfall would have the intoxicating color it’s famous for.

Catching up to M, we dashed along together. Suddenly, a creek crossing marker pointed ahead. Only, instead of the expected stepping-stone hops, fast current rushed by. Others from our group were ahead; they must’ve crossed here, too, We linked arms, wading carefully against the current’s push. We were knee-deep when its strength broke us apart, sending us swimming.

In a flash, I thought of the boulders and wood strewn downstream, knowing the cold water would push me into danger. My knee bonked on a rock, and I worried, “Please don’t let my head be next.” The adrenaline fueled my muscles, and we furiously swam to the bank, soaked but relieved.

Panting, we wondered how the others had crossed. Hustling to catch them, we followed the trail-- until it led back across the creek. My stomach dropped at the sight of the swirling current. We opted to bushwhack in hopes of finding a spot upstream.

The flooding creek

Carefully picking through the cactus-studded brush, we finally spotted our group across the creek. They’d never crossed, opting for a scramble instead. With no rope to help us cross, they continued up while we attempted to keep pace. Soon, the stumbling through the cacti became too tricky. Noticing the time, we made the call to turn around; no waterfall for us.

Yet, there were still no safe crossings, and now far more water coursing through the creek. M and B identified a spot to try, but the voice in my head screamed at me to stay on land. My knee throbbed, though my ego was bruised even worse. My heart fluttered at the tangles of current beside me; I was adamant we wait for help before attempting another crossing.

Soon, friends came back our way, also bailing on the falls mission. The tightness in my chest loosened; there was power in numbers. We devised a plan to create a link of arms extending into the water so that we could swim partway across and have it catch us downstream. Nerve-wracking, but the best option—until we realized the current was too strong. With no other option, we continued crawling through prickly brush, the temperature plummeting as clouds encroached.

Stuck on the far side. Photo by Kristen Tedrow

When the shore eroded into water and morphed into sheer cliff, we stayed put while the others hiked back for gear. All we had was a backpack with a little water and two snack bars. We nibbled them, huddling to stay warm.

To my dismay, B and M debated alternative crossings. Desperate for a sense of safety, I begged them to stick to the plan and wait. Waves of dread washed over me as I watched them tiptoe along rocks, debating the consequences of the rapids downstream. Yet, I felt more insecure about myself.

After all, they had more experience and comfort in water than me. I was no stranger to judgment from men in the wilderness. Would they blame my unease on being a woman? Was I a “nag”? Did they think I wasn’t skilled enough to be here? Not “chill” enough to boat with in the future? A light rainstorm rolled in, and my goosebumps and I took shelter in a shallow cave.

Two hours later, our friends returned with PFDs, lining them across the river using throw bags. The goal: Wade as far as possible while grasping the rope, then hang on and let the current swing us across.

At my turn, I cautiously waded through above-waist current, determinedly clutching the rope. When I lost footing, I held on for dear life. Unfortunately, I’d forgotten what I’d learned in a swiftwater course years ago. Rope on the wrong shoulder, I gator-rolled in the current, and the rope twisted around my neck. I kept holding on, horrified the rope would either suffocate me or snap my neck.

Kyle jumped in for a tethered live-bait rescue, lifting me to shore. My body shaking but mind relieved, I felt buoyant when B made it across safely.

“Phew! We’re okay!” I thought… Until we learned the rest of our hikers were trapped further downstream, forcing another roped swim. We headed downstream, in awe of the now-torrential creek below. Instead of a calm, Gatorade-blue trickle, we had a raging Class V river—an indisputable flash flood.

Our crew rescuing ourselves. Photo by Kristen Tedrow

Thankfully, the next crossing went safely for all. But we acknowledged, bluntly, how dumb we were. How had we not seen it coming? It hadn’t rained recently enough to consider flash floods, though the water’s color should’ve been a giveaway. It’d happened subtly, yet suddenly.

We crawled down ledges from the plateau above the canyon mouth, stunned at the deluge below. Our rafts, clinging by cams in the wall, bobbed in whorls of current that had once been a calm pool.

Boat barge waiting for the rest of us to return. Photo by Kristen Tedrow

A taut line stretched from us to the boats. One by one, we hand-over-handed across. At my turn, our trip leader Judy suggested I cross with B. Thank goodness she did.

Losing footing mid current, my legs flopped uselessly as I gave the rope a death grip, mindful of rapids below. With every pull on the rope, I felt it burn my skin. B kept one hand on me, the other on the rope; together, we dragged ourselves across. After four swims, exhaustion settled in my bones.

The final crossing, where I got my rope burn. Photo by Kristen Tedrow

With the sinking sun a reminder of our dwindling time, we began the process of untying boats. Once detached, rowers had to pull hard and fast to avoid mid-current rocks. Euphoria washed over me when strong strokes got us all through unscathed, our entire party reunited on the Colorado.

With darkness approaching, we took the next camp, threw dinner on the stove and sat around the firepan to debrief in the chilly March evening…

What Rescued Us

Practical experience: A mix of experienced boaters, climbers and first responders was key in setting up rope systems and plans. With excellent delegation and execution, I couldn’t have been in better hands for swims.

Teamwork: Care for each other was top-notch, from encouragement to genuine “Are you okays?”. The trust we’d built over weeks on the river kept the rescue efficient and as safe as possible. Each person made a positive difference.

Using resources: Brian smartly scrambled to the Colorado early on, shouting to another approaching party. They helped barge and cam rafts in hopes of preventing them from blowing out the eddy. Others gathered snacks and dry layers to give swimmers.

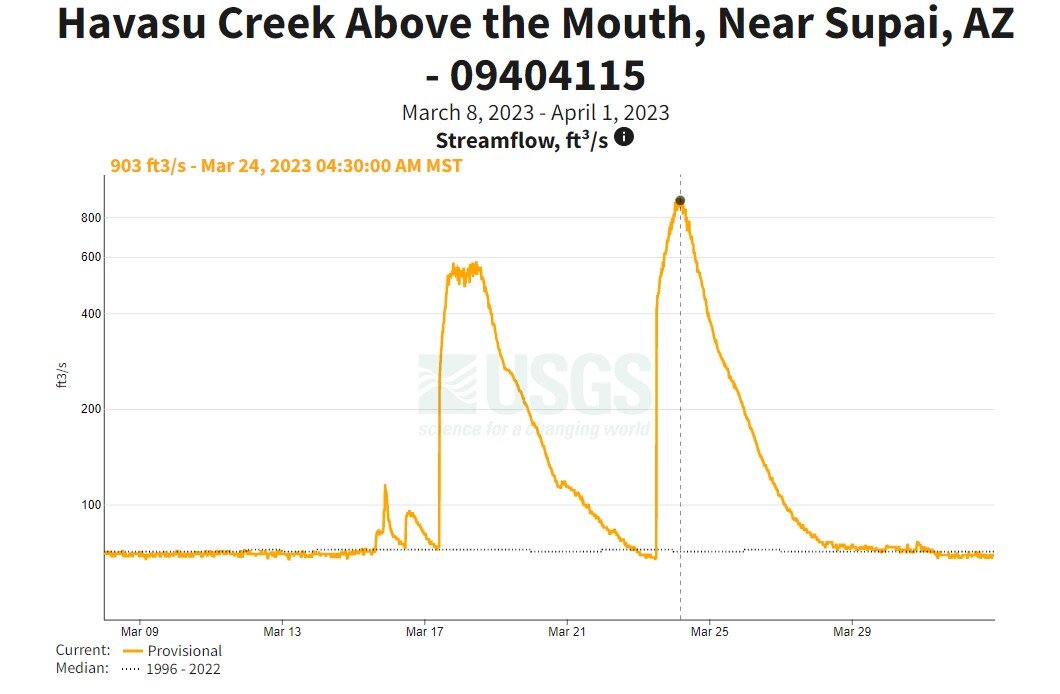

USGS data marking the flood

Big Lessons Learned

Complacency kills. After two weeks, we’d grown too relaxed. Although we’d only planned to be gone three hours, we should’ve brought supplies, like clothing and food, to last longer. We should’ve taken safety gear like a throw bag and a PFD in case of emergency.

Speak up. As the least experienced, most uncomfortable and only woman stuck on the other side of the creek, I was nervous about vocalizing my needs and concerns. On many expeditions, it’s helpful to default to the most conservative opinion in the group for safety, rather than the most confident.

Practice skills. No wilderness training is one-and-done. Had I remembered swiftwater rescue techniques, I could’ve avoided the rope wrapping around my neck. Plus, the rope burn under my armpit was incredibly painful for the remainder of the trip. Commit to practicing skills between trips, even if you rarely use them.

Build a solid team. Assembling a crew with a variety of experiences and backgrounds gave us the knowledge and practical skill to facilitate our own rescue. Every member was vital; even folks without whitewater experience were crucial to emotional response and support.

Acknowledge heuristic traps. How could 16 experienced boaters miss the potential signs of flash flooding before it was too late? Blame it on the human brain. Many accidents happen not due to lack of knowledge or experience, but because of ”heuristics,” rules of thumb the brain uses for mental shortcuts based on past experiences. Subconscious shortcuts based on past situations or existing social dynamics can cloud judgment by ignoring the complexities of the current situation’s hazards and risks, falling prey to “heuristic traps.” For example:

Familiarity Heuristic: This hike appeared similar to other desert creek hikes we’d done over the weeks and other trips. We assumed it would unfold similarly.

Time Pressure Heuristic: The feeling of “We need to be quick to see the falls” led us to cut corners, like not bringing gear and not minding the water level.

Recency Bias: We figured since we hadn’t gotten rain in two days, we didn’t need to worry about flooding. We overlooked other data based on what we’d seen most recently.

Scarcity Heuristic: The hike up to Beaver Falls felt like a “once in a lifetime” hike that none of us wanted to miss out on, potentially blinding us to signs of what, in hindsight, felt obvious.

A magical place

The Canyon’s Legacy

The evening of Day 16, I sat in the sand alone by a repurposed groover and selection of ammo cans tucked into a cove at the edge of camp. Affectionately nicknamed “Tequila Beach,” this camp is just below Lava Falls, which typically marks the trip’s climax. With my knee still swollen and rope burn aching, I sighed in relief. My group and I were safe and happy, through the biggest hazards with a new appreciation for the forces of nature that drive them.

My headlamp cut through the dark, illuminating hundreds of scraps of paper stuffing the metal containers. I pored through entries scribbled over the past decade, struck by the humanity behind each message: notes of post-Lava celebration, acknowledgments of fear and lines gone wrong, apologies to former lovers, a letter to a baby in the boater’s womb, recaps of trips past and hopes for the future.

The common thread? How the river transformed them as a person.

At that moment, I connected to thousands of river runners scattered across the planet, all committing to becoming better humans because of their experiences in the Grand Canyon. The commonality of the human experience through the waves we row and the words we write struck me: every soul who floats the river simply wants to taste the richness of life and emerge safe.

I cried at the intense grief and joy that can coexist in life’s current, for the boaters who came to the Canyon searching for one thing and leaving with something unexpected, for the boaters who’d see countless more river miles and for those whose trips were numbered. I cried in relief that through a flash flood, nobody was badly injured or killed.

Human connection is powerful. Water can be even more so.

The burn scar on my arm remains as a reminder of these lessons. The splotchy border of new, pink skin reminds me to never take knowledge or experience for granted.

Perhaps the scar will fade completely over time-- but the impact on my future trips is permanent. Nature has a way of leaving her mark on humans, hopefully for the better. She taught me to share my voice, to think critically, to never stop learning.

When I got back to what the groover logs dubbed the “default world,” everyone asked me that loaded question: “So, was it life-changing?”

Yes, I’d say so.

Rowing out on our last of 21 days in the Canyon.